To unlock rich data, lock in groundwater rights, markets

On August 22, attendees at the 4th Annual Water Data Summit at UC Davis spoke at length about the uses of, need for, and benefits from harnessing more and better information about water use: “Data touches nearly every inch of the water sector, and the importance of it as new innovations and management practices modernize our water systems cannot be understated.”

But if information is vital and wants to be free, why are the most important data points about water often proving so costly, in time and effort to access? Because of political uncertainty.

Water utilities may own, access, and control secure data about urban water use. Yet groundwater is proving a far more distributed and thus difficult beast. No one knows how many wells there are, let alone who uses how much groundwater, where, from what depths and for which purposes, when.

Water utilities may own, access, and control secure data about urban water use. Yet groundwater is proving a far more distributed and thus difficult beast. No one knows how many wells there are, let alone who uses how much groundwater, where, from what depths and for which purposes, when.

The decentralized nature of groundwater makes it impossible for any single entity to manage. It sets up a wicked problem, and classic “tragedy of the commons.”

AquaShares founder James Workman argued that this information about what has increasingly become the source of more than half of all water use in the state would remain concealed — unless well owners can feel secure.

AquaShares founder James Workman argued that this information about what has increasingly become the source of more than half of all water use in the state would remain concealed — unless well owners can feel secure.

“Irrigators in particular must know that more knowledge about the wet stuff they pump from the ground — the quality, quantity, timing, and depth — won’t be used against them,” he said.

“Already hostile to metering their wells, farmers fear information could be redeployed to reduce access, levy unilateral fees on a free asset, or reveal sensitive information that could benefit competitors.”

This reaction is perfectly normal, he added. We don’t even share our favorite fishing holes, so who wouldn’t keep secret from government the most valuable source of our livelihoods?

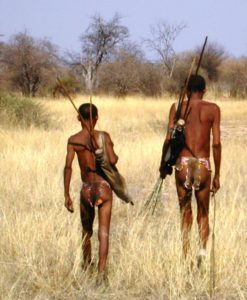

But Workman showed how traditional and modern rights-based resources water conservation exchanges — Arabian aflaj, Persian qanat, Balinese subak, and the !xaro system of Kalahari Bushmen — had unlocked abundant and reliable data to flow like, well, groundwater.

But Workman showed how traditional and modern rights-based resources water conservation exchanges — Arabian aflaj, Persian qanat, Balinese subak, and the !xaro system of Kalahari Bushmen — had unlocked abundant and reliable data to flow like, well, groundwater.

The difference? In these other formal and informal cases resource users had been able to define, defend, and divest secure access rights. True, these systems didn’t emerge overnight, Workman allowed. They evolved.

But we can learn and apply the core lessons for how they took shape to guide our own design of socially equitable, ecologically sustainable and economically efficient groundwater markets in California.

This process may be contentious, but it endures if anchored on the ancient principles of transparency, transactions, and trust.

“The only thing more valuable than water is trust,” Workman concluded. “Once stakeholders feel secure that their fair share of groundwater won’t be taken away from them by someone else, sharing the same aquifer, they do more than allow access to data. They demand more of it, and are willing to share it.”