The Rights-Based Revolutions Beneath the Surface

Political struggles over flows for spawning salmon have led Californians to imagine that the interests and outlook of commercial fishermen and irrigation farmers are diametrically opposed.

Yet they may have far more in common than they realize. AquaShares has long argued that food producers offshore and on land both depend on an invisible and fugitive resource. They both confront the tragedy of the commons.

And they both can and indeed must self-organize virtual markets to trade clearly defined and equitable allocations of the resource they share.

How? AquaShares walked through this strong but often hidden connection in a recent 40th anniversary issue of PERC Reports, the magazine of the Property & Environment Research Center.

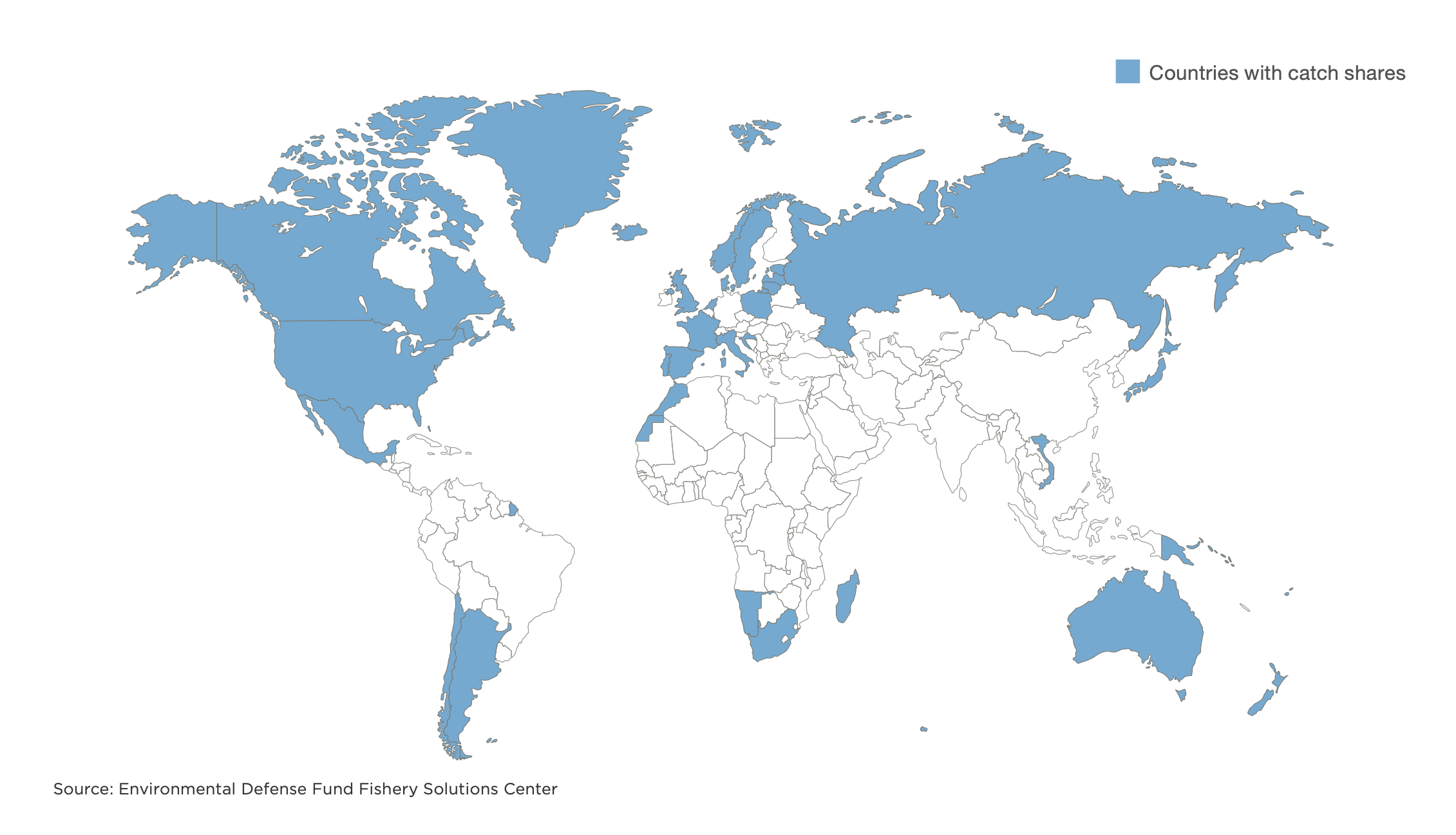

In the article — The Rights Based Revolutions Beneath the Surface — Workman argued how, through clearly defined rights to their shared and invisible natural assets, fishermen and irrigators alike reverse a race to the bottom.

He focused on the lessons from California’s Pacific fishermen, who have replenished hundreds of species back from depletion and national disaster status. He then showed how the same approach to groundwater could heal aquifers throughout the state.

After all, he wrote, “humans cannot live on fish alone. Most of our drinking water and half of our irrigated food comes from groundwater. Humble, earthy, and hidden from view, groundwater feels emphatically unsexy. It lacks the romance of fishing, the jolt of energy, and the scale of climate change. Except when millions of wells run dry.

“That’s not a hypothetical; it’s happening in my home state of California. Drought’s impacts are well known on the surface, as the state dammed, diked, diverted, dried, and silenced rivers in an unprecedented replumbing operation over the past century. Less appreciated, until recently, is how much urban, rural, and natural life depends on functioning aquifers….

Offshore fishing and inland farming may seem worlds apart. Yet both activities, in their own arenas, are susceptible to the tragedy of the commons. In both, cheap energy and new technologies lower the barriers to extract wealth from an invisible common pool. To slow, stop, and reverse depletion, both must find ways to share and steward this precious and literally “price-less” asset beneath the surface.

As with ocean fisheries, the typical response to groundwater depletion is to call for coercive regulations that force all users to pump less. Aside from the political obstacles, there are as many legal and practical challenges to this approach as there are wells. Without bottom-up collaboration, it will remain difficult to even figure out whose wells are pumping how much and from where, let alone force people to cut their water use.

As an alternative, today my partners and I have begun to apply the same rights-based approach to groundwater that has worked so well in fisheries. Our company, AquaShares, helps water users design and operate water savings markets in groundwater basins ranging from Sonoma County, California, to Marrakesh, Morocco. We work with communities to set collaborative goals that are fair, inclusive, and build resilience. To achieve these outcomes, we design accountable, yet flexible credit trading systems that limit market power, integrate the human right to water, ensure efficient trading, and protect groundwater-dependent ecosystems from deeply rooted forests to shallow ephemeral wetlands.